Graham Gage, PT, DPT

This month we will pile on about the benefits of resistance and plyometric training.

To start, let’s emphasize the importance of resistance and plyometric training. One of the best ways to become a better runner is to run more.1 One of the best ways to be able to run more is to avoid injuries. One key component of injury prevention, along with smart/progressive load management and optimizing recovery, is developing the physical capacity of your tissues (bones, muscles, tendons). There is a substantial and constantly growing body of literature to support the benefits of resistance and plyometric training for improving bone density, muscle size and strength, and tendon health.

Let’s repurpose an old proverb for our needs today: “The best time to start a resistance training program is 20 years ago. The second best time is now.” However, committing to a new habit can be daunting. Especially for those of us who are also committed to increasing our running volume during this time of year. There were some great insights about strength training in last month’s blog post that I will summarize here:

- Aim for twice a week.

- Consistency is key.

- Don’t push yourself to failure on an exercise if you don’t want to be overly sore.

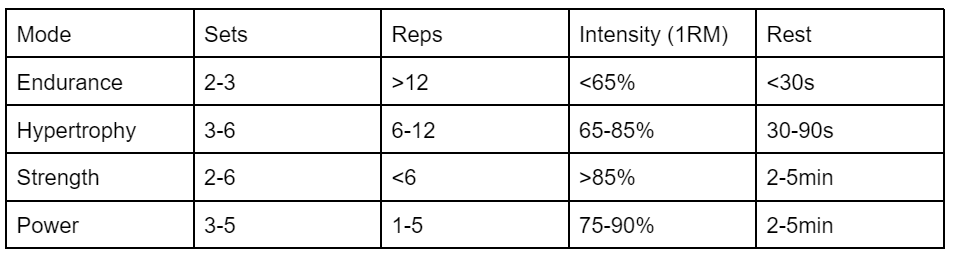

To further understand how to think about strength and plyometric training, we will include a table that is modified from the seminal text Essentials of Strength and Conditioning2.

Novice lifters should start in the endurance zone. This high rep, low weight scheme will allow the brain and body to communicate effectively to achieve strength gains via neuromuscular adaptations. For plyometrics, this might look like hopping drills.

As a lifter advances beyond the first 4-6 weeks of a lifting program they should gradually add weight and reduce the number of repetitions in each set to move into hypertrophy parameters. At this stage strength gains may start to come from muscle tissue adaptations. For plyometrics, one might be shifting towards more explosive endeavors like box jumps.

Within 8-12 weeks of initiating a strength routine, one might feel comfortable enough with their technique and capacity to start pushing heavier weights and moving into the strength and/or power parameters. Plyometric exercises in this phase might be more intense, such as drop jumps.

On a yearly basis, an athlete should be moving in and out of each of these phases, following a concept called periodization. Based on our location here in Missoula, it would make sense to allow the changing of the seasons to dictate a change in the training cycle. For example, a runner may take a brief off-season at the end of summer, then initiate a training cycle throughout the Fall to peak for skiing season. This variation in training intensities and modes over the course of the year will prevent over-training and will help individuals bust through plateaus.

One other aspect about living in Missoula that should not be ignored is the fact that our community has a large and well-trained population of fitness and healthcare professionals (insert plug for Alpine PT here) who are more than capable at helping you become confident and competent with managing your health and athletic performance. Taking the time and committing the resources to learn more about these concepts is an investment in yourself and will only serve to enrich your existence in this beautiful place!

- Yamaguchi, A., Shouji, M., Akizuki, A. et al. Interactions between monthly training volume, frequency and running distance per workout on marathon time. Eur J Appl Physiol 123, 135–141 (2023).

- Baechle, Thomas. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning. 4th ed., Human Kinetics, 1989.

missoulamarathon.org >>

missoulamarathon.org >>