To whom it may or may not concern,

The Bigfoot 200 is impossible. Nevertheless, I finished the Bigfoot 200. How do you finish an impossible race, you may ask? You cheat, legally. Cheating legally isn’t technically cheating, but it sure feels like it. How can you too cheat legally? Get yourself actual pacers and a real crew. The Bigfoot 200 was my first race with both, and let me tell you, it was magic.

The Bigfoot 200 proved once and for all a lesson that I barely started to learn in 2022, at the end of the Cocodona 250, Ultra Running is a team sport. As much as I wanted it to not be true, it is. My western roots and “rugged individualism” chafed at the idea of needing anyone, or anything. I had run all my races before without pacers, with only my wife and 6 year old son to say hello, once a day, in the daylight. I didn’t need anyone. I would be fine. Except, after mile 197 at the Cocodona 250. I wasn’t “fine” then. I wasn’t rugged or individual. I was destroyed. I was done.

Heading into the Bigfoot 200 training season, I had little to no concern about finding pacers or a crew. I had sent out a quick text to a few friends to see if anyone was interested. When all I got was a lot of “no”s it didn’t faze me. Months went by, I asked two more people. Everyone said “no”. A lot of people said they couldn’t keep up with me, which we all know is a lie, because most often, I am painfully slow. When a soon-to-be retired friend, Mike Zielinsk, asked me if I needed any help at my race, I said sure, maybe. “If you can help, then great. If not, no big deal. No pressure.” I feigned. Mike had never run an ultra, never seen an ultra, the closest he came was following me online when I ran Cocodona 250 last year. Mike had no idea what he was getting into. Mike was blissfully ignorant of the hardship he was about to endure. Mike was perfect. Another friend, John Hart, mentioned he might like to pace me, if he was healed up, if his long runs went well, if his back-to-back long runs went well, and if he didn’t get in the 50k he was on the waitlist for, and if he could find a ride back to his car, and if and if and if. I said, “If you can pace, great. If not, no big deal. No pressure.” I was fooling myself, but what other options did I have?

Weeks and weeks went by. Mike recruited his son to help him with driving and navigation. The course driving directions revealed the unparallelled remoteness of the course. One hour and forty minutes to drive 20 miles, how could that be? No cell service on the entire 200 mile course, except at the finish line? No communication between stations except by HAM radio? What exactly was I signing up for, invading the borderlands of a third world country? Where in 2023, in America, is there a piece of land with 7,437 feet of gain in a sustained climb, from one creek bottom to one ridge? That is 1000 feet deeper than the Grand Canyon. I felt like they might be over-stating their case. I felt like they may have fudged their numbers to scare east coast natives and city slickers. It turned out, they had not.

With race day rapidly approaching, John began to check off his “if” list. His long run went well, his back-to-back long runs went well, RATBOB went well, he didn’t get into the 50k. So, was he pacing me or not? He was still unsure. “You might see me, you might not” was John’s non-answer. “When I come out of the woods from my backpacking trip I will message your crew and see if I can get a ride back to my car” was his self proclaimed plan. To add to the complications of vehicle transport was a road closure smack-dab in the middle of the route due to a mudslide. Bigfoot was a week away and I had a crew who had never seen an ultra, and a pacer who was not yet a pacer. Last minute, I got a lifeline. Kristina Pattison, my coach, had another potential pacer. A young guy, full of spit and vinegar, who wanted to talk for 24 hours about how to get “mentally tough” and then see someone actually trying to get “mentally tough” and then make the decision on whether or not he actually wanted to achieve said toughness. (Seeing it done has a tendency to make you have second thoughts about such daydreams.) Not that I am officially tough, but I have seen four children born, without drugs, and I now know what tough looks like. I can tell you, I would never sign up for that. John started to flirt with actually showing up. Grant said he could drive his car back to the start line to pick his car up. We almost had it figured out, and tomorrow was the race start.

Ten AM on Friday August 11th came lightning fast. We camped at the start line, got almost no sleep from the noisy neighbors arriving late in the night and rising early. Here we were, ready, taking the Destination Trail Race oath “If I get hurt, If I get lost, If I die…It’s my own damn fault”. A group photo later and we were counting down from 10. The race started, and the slowest, most gigantic herd of turtles set out at a pace that would make a snail ashamed. This barely even qualified as walking. I always start in the back of the pack, because I am slow, and I hate to be passed, but this was beyond ridiculous. I could not possibly move this slowly. Too late. I would now have to pass over 100 people in order to run a single step. I began the process, and I felt great.

We started straight up Mount St. Helens, into the blast zone. No trail, just posts to guide us, through an endless boulder field, interspersed with sand and ash and gravel. Zero shade, and temps approaching 100. Seven hours of direct sunlight, over 29 miles, of sweat, and ash and sand. A virtual moonscape, an other-wordly landscape enveloped us. It was awesome, it was strangely beautiful. It was freaking hot. And I had forgotten to pack my electrolytes in my start pack. First big mistake of the race. I started to cramp in ways that seemed impossible. A cramp from my big toe, up my shin, that curves around, up my hamstring, into my glute, how is that even possible? My left leg felt like it would collapse under me. I began to have serious doubts about finishing. I felt like I broke my leg. What the heck? What kind of a greenhorn, rookie, wanna-be forgets electrolytes? I found what appeared to be some electrolyte tabs dropped on the trail. I threw them in my water bottle. Their legality and narcotic properties may have been questionable. I didn’t care. I pressed on, I sat in a freezing cold creek, and I could run again. My heart rate finally came down. I ran uphill to my first drop bag, and the electrolytes within, at the aptly named Windy Ridge. I found my wife and son waiting for me. What a pleasant surprise. I took a bunch of salt tabs. I ate everything. I ate more. I had an ice cold Coke. I was ready to conquer the world.

Everything went great on a long descent, I pressed on to make it to mile 46 and my first crew stop, at Coldwater lake. I began to play leapfrog with someone who seemed to be an impossibly old man, power hiking. Despite his apparent aloofness and the fact that he almost never actually “ran”, he continually passed me every time I stopped for anything, for any amount of time. Little did I know that the Grey Ghost would haunt me till the end of the race, or how powerful his hiking would be. I wanted to make it into Coldwater Lake in daylight, without using my headlamp. I could sleep there if I wanted. If everything was going well, I might continue on through the night to Norway Pass. I missed sundown by 10 minutes and barely had to pull out my headlamp to avoid traffic coming into the parking lot at Coldwater Lake.

Mike and his son, Michael, had their debut as an ultra crew at Coldwater. I barked orders, pointed, instructed, and specified. I went into great detail about the precise location in my running pack that each item would be packed. I requested all available hot food. I wanted to eat, change my shoes and try to lie down. I wanted everything. I wanted it now. I was a spoiled little brat. Mike and Mike, or “The Mikes” as they would affectionately be dubbed by John Hart, snapped to it and executed with precision. What usually takes me 20-30 minutes alone, took them approximately 4 to accomplish. It was time to try to sleep. I had them set a timer for 12 minutes. I laid down for 10. I wasn’t tired. So I decided to continue into the black. It was amazing: the Mikes, on their first try, with zero experience or prior knowledge had got me in and out faster than I could have imagined. This was cheating. No wonder all those people have their Sprinter vans full of teams of people. I was always self righteous and arrogant about not having a crew. I used to sing Janis Joplin’s “Lord won’t you buy me a Mercedes Benz” as I ran past all the professional crews in their $80,000 Sprinter vans. I was just jealous. This was magic.

Into the dark night of the soul. The 5600 foot climb to Norway Pass took place in under 10 miles. It was through several large bowls, or cirques. A line of headlamps, resembling the Yukon Gold Rush stairway to heaven, climbed the pass in procession. Up impossibly steep knobs, the lights clung to the sides of cliff edges. Then dropping off the backside of the bowl, the lights disappeared over high mountain saddles, to reappear again at impossible distances, across huge canyons, only to repeat the process. Every time I crested a ridge and saw the repeat of the procession, I thought I had made a wrong turn in the dark. I felt like I was going in circles. The great horseshoe patterns continued. Three times we topped out on ridgelines, only to repeat the process.

Finally when I knew all climbing was done, for certain, I climbed under the last stunted spruce tree below the ridgeline to escape the wind. I was ready to sleep, it was soft and almost calm. I put on my hooded puffy jacket and crawled into my emergency bivy. I slept for an hour and slid out of my bivy into sand. No wonder it was so soft. Unknowingly, I had partially filled my underwear with sand upon my exit. This would bear some serious consequences. I ran with the rising sun down from Norway Pass to the aid station in another impossibly large curve, around a giant canyon, in an almost complete circle to the aid station below. I thought it was a cruel joke, but upon further examination, after the descent, I realized the entire canyon was a cathedral of sheer cliffs walls, without any possible descent. My timing was impeccable. Amanda and my son Amos were there to meet me, early in the AM, and to top it off, I got to use a “real bathroom” to take my first dump of a multi-dump run. A special treat, only an ultra runner can understand. Thanks to the Mikes, I was already ahead of schedule. Amanda got me food. My back felt weird, under my underwear band. I had her take a look. “Why does my back feel weird?” I asked. “Because you don’t have any skin on it” was her reply. The sand in my underwear band had rubbed off my epidermis. Luckily I had Amanda to tape my back. I am 99.9% sure it is impossible to tape your own back. At least not effectively. I laid down in the sleep station and took a quick 20 minute nap. I was miraculously ready to run again, and I did.

Norway Pass to Elk Pass was a cake walk compared to the climb to Norway Pass, but the steep climb out of the aid station gave me second thoughts about leaving the comforts of the cot. I got it over and done with and started the descent to Elk Pass, and the possibility of my first pacer, John “Wasatch” Hart, the wild man with the “off the grid” personality. John, the self-proclaimed “trail running curmudgeon”, the hater of all things electronic and all excuses. John, the endless giver of shit, and one of the funniest guys I know. (all at your expense). The one defining characteristic of Wasatch, that excited me the most, was his toughness. He had never DNF’d. His racing philosophy matched my own. He told me when we met that he had two options when racing, he would either finish, or leave in a body bag. Truly a man after my own heart. In my mind, all these wonderful characteristics would make him the perfect pacer. In reality, it would make him a huge pain in the ass, and a better pacer than I could have asked for.

When choosing a pacer you must differentiate between love and “tough love.” You are going to need a large dose of the latter and almost none of the former. While running for 43 hours from mile 80, to mile 165, I did not value any of John’s “tough love.” Not a single ounce of it. I secretly hoped he would drop out. I harbored thoughts that he was “ruining my race” and “taking away from my experience.” I was wrong of course. But my sleep deprived, weak mind, could not comprehend that he was helping to propel me beyond my dream goals.

Let me pass on some of the priceless ultra running advice I received during the 36 hours with John. “What are you doing? Stop messing with your shit!” “What is in your pack? You don’t need all that shit. Why do you have so much shit?” “You don’t need all those electronics! What are those even for?”, “You don’t need to send them a message, they will figure out where you are, keep going!” “There is no place to lay down! Stop looking! Put your head down and look at the trail. I will find you a spot to lay down. Keep going!” “It is flat”¦Shuffle!” “It is down hill, let gravity assist you! Start running.” “You do not need to sleep, keep going”. I heard each of these priceless pieces at least 100 times. Each was followed by a variation of the same statement. “I am a slave driver. You are going to hate me when this is over.’ That statement ended up being the only one that was wrong. I, in fact, love John Hart. He saved my race from mediocrity. He did what I hoped he would do. He taught me to race and not just run. A thousand thanks John.

The 86 miles with John was a sleep deprived blur, but two things are seared into my memory. Sitting in an ice cold creek until my legs were numb and my wife Amanda saving the day. After about 24 hours my pace slowed considerably. My legs were already cramping and I made the mistake of sitting in a camp chair to rest and eat at the Road 9327 aide station at mile 90, where we had met the Mikes. The Mikes were staged a couple minutes up the road but were late arriving to the aid station because I arrived a little earlier than expected, and we had some electronic communication failures between our InReaches. I had fallen behind on my eating and drinking schedule because I couldn’t stop talking to John. I could barely stand or walk when we went to leave the aid station. I decided to sit in the frigid creek next to the aid station. I got in and sat until I couldn’t feel my legs. When I emerged, I felt like a new man. John secretly whispered to the Mikes “He has new legs! He’ll be fine.” And miraculously, I was fine. The pace increased on our way to the Quartz Ridge aide station at mile 126.

My wife Amanda saved the day at Quartz Ridge, just by being there. She was barely there, but she was there. As we descended down onto the paved road that led to the Quartz Ridge aide station, I saw my wife’s car pulling away. Desperate and afraid that she was leaving, after an overly long wait with a 6 year old, John and I sprinted down the road, yelling at the top of our lungs and waving our arms. John’s sprinting was actual sprinting, unlike mine, and he quickly overtook Amanda’s vehicle. Unfortunately, Amanda had never met or even seen John Hart. So, down the road came a dirty, long haired hippie wearing a visor, screaming at her, “We’re Here!” “Good job” she responded in subdued fear and confusion. “I’m with Tom! I’m John!” He exclaimed to help alleviate her confused expression. What we thought was driving away, had actually been her finding a parking spot. She had just arrived, in the knick of time. We rolled into the aide station and began looking for my drop bag. Several people had the identical sack, but none had my label. My drop bag was missing! Or perhaps, I had forgotten a drop bag. Regardless, I had no calories, no gels, no stroopwafels, no salt tabs, no caffeine pills, no backup battery for the electronics that John said I didn’t need. I had nothing. Except, Amanda had back ups of everything, in her car. Once again, the same lesson rang true. Ultra Racing is a team sport. It took my wife being at that aide station to help me to continue to achieve my goal. I was running, but “we” were racing. Mike, Michael, Amanda, John and Grant and I were racing. We were racing to pack my pack, fill my water, feed me, fix my feet, and point me in the right direction. We were a team, and this team was crushing it.

John and I ran, shuffled and power hiked into our second black, moonless night. The Grey Ghost had appeared to argue with me about the route down the paved road. He didn’t believe my watch. I learned from John that the Ghost was no other than Carter Williams, the life long rival and nemesis of not one, but two Missoula runners. Carter is 65 years young and had been ultra racing for decades. Apparently, he likes to wait until the very end of the race to make his move and beat his opponents in the last ten miles. I still had over 70 miles to go, so I didn’t think much of it at the time. I hit my “third wind” and began to almost out pace John. “I can hardly keep up with you. What got into you?” John exclaimed on several occasions. I had no idea, but I liked it. We pushed on to Klickitat, mile 165, and my second pacer, Grant Cunningham. John looked forward to sleep. I was ready for the supposed ease of the last 45 miles, with a cumulative elevation loss and 75% of the climbing already out of the way.

Klickitat aid station had my full crew and both pacers. It was a party. Barbie themed and fun, the experience energized me. After getting my feet re-taped, and receiving the high compliment that my feet were “As smooth as a baby’s butt”, I was ready to roll into the third stretch of darkness. Starting out with a great downhill section, I mistakenly thought I wasn’t tired. Once the final long climb of the race started, I realized I could hard stay upright. I was falling asleep standing up. Grant was the polar opposite of John, kind and accommodating . He was more than willing to slow down, and to help me look for places to lie down and sleep. Once we would find the perfect flat spot, with soft grass, and shade, we would lie down. Immediately upon closing our eyes, the horrid black biting flies would descend, in hordes. Hundreds of tiny jaws ate at my flesh. Just enough pain, in a thousand locations, made sleep impossible. We would abandon our perfectly picked spot, after 5 minutes or less, and trudge along looking for another spot. Hours passed. We tried windy ridgelines, to blow the impossibly large flocks of flies away, to no avail. We tried full sunlight to dissuade the legions, with no luck. The flies drove me forward. Twice the slave masters that Wasatch had been, the relentless flies spurred me onward. Never in my life have I wished such total and utter destruction on any living being. No wonder they call Satan the Lord of the Flies, these cruel creatures were truly his minions. The heat climbed, eventually reaching 108 degrees Fahrenheit. The exposed ridge sections had great views, for an oven.

As a last cherry on top of the 43,000 of elevation gain we had already ascended, we did an out and back, in shadeless sunlight, to Pompei’s pillar, to see all the surrounding peaks and supposedly contemplate our “journey”. When we didn’t stop and spend the proper amount of time “contemplating our journey” the photographer, and unbeknownst to us “curator,” made us return to the summit to look at and point at each of the peaks we had climbed or passed, so we could “relive” our experience. I however was not ready to “relive” my experience, because, as far as I was concerned I was still in the middle of living my experience. Carter “Grey Ghost” Williams joined us for the climb and was even less enthusiastic about the contemplation ritual than we were. He was also more outspoken in his contempt. Complaining was not what I would have expected from a seasoned ultra runner, especially one who was often beating me, despite our two decades of age difference, but as we joined together for this section I would hear many monologues. This race sucks, I am never doing it again, this blowdown is ridiculous, why didn’t they clear this section. And more often than not, he would argue with me about navigation. My watch was wrong, I was going the wrong way, there were no flags in that direction. I should have left him lost and headed the wrong way. He was getting on my nerves, and bringing me down with him. But, instead I would yell back to him when I would find a course marking, get him turned around, and wait until I could see he was on course. He seemed confused and sleep deprived. This was obviously, not entirely true. We hit runnable trail, and he breezed by me. The man was a machine.

We hit the grassy gradual downhill logging road that I had been looking forward to for 188 miles. This I had told myself, is where I would shine. Downhill running is my jam, and besides eating, is one of my only strengths as an ultra runner. However, when I hit this pristine runnable road, I couldn’t run another step. My feet were on fire. The pain was unbearable. I felt like all the skin had been rubbed off the bottoms of my feet. I tried walking barefoot in the grass, walking backwards, and cleaning my feet. Nothing helped, and I was helpless. Would the final 19 miles of my race take me 8 hours? I couldn’t stand the thought. Grant was gracious as always, even though he had been out of water for hours. We finally hit a good water source with a sweet sitting spot. The conversation never died over the 45 miles. An articulate and thoughtful man, Grant gave me hope in humanity. We had only met briefly before his pacing me. We ended up with countless things in common and many shared interests. The talking was a perfect distraction from the pain, and his humor made the flies, the scorching sun, and painful feet laughable. His attitude outshined the Ghost’s gloom. We sailed on in a continual banter concerning mental toughness and archery hunting.

There was one final choice to make, to be in pain or to be in pain. To be in less pain, for longer, or to be in more pain, for a shorter time. To hobble-walk, or to really, actually run. I needed this to be over; I had come, I had seen, and I needed to conquer. I chose more pain, for less time. But first, we must fuel. Owen’s Creek had the best bacon cheese burgers I had ever tasted. Lettuce, tomato, Onions and fresh bacon, topped with a fried Egg. I thought I had died and gone to where dead people go. I complimented the cook, who told me his creation was called the “Davy’s Burger” and could be obtained at my leisure at the “Hoot and Toot”, a local Burger stand near Packwood, WA. As we talked the Grey Ghost slipped from the aid station, I thanked the cook profusely and geared up for a proper suffer fest and some Type II fun at its finest.

Grant had been curious about how to finish a one hundred mile plus race. We spent hours in a long discussion concerning mental toughness, and how it was fostered and developed. We speculated and postulated, but the time for theories was done. “Now I will show you how to finish” I told him. “Let’s set a timer for 10 minutes. We will run as hard as we can for 10 minutes and then walk for 1 minute.” We commenced our timing. I started running on my fire-scorched feet. Everything hurt, and I ran. Everything hurt more, and I ran. We ran faster. Then, when I thought I couldn’t take another step, it hurt less. Our pace began to increase. We breezed past Carter Williams, and were unable to make out his comment as we passed. Something akin to “Now you’re running?”. I can’t be sure. We ran one, then two, then 6 miles. My fourth wind was a miracle. My body produced endorphins I didn’t know I had. I messaged John and my crew, we would be there hours ahead of our projected pace. Two hours and thirty minutes more. In my mind, I would finish at 12:30 am. Too bad no one would receive the message, or perhaps they didn’t believe me.

Eleven miles of pavement is not my friend, no matter the day or time or weather. The elevation chart showed a continual downhill. The spreadsheet showed a measly 342 feet of gain for the section. It sounded easy. When we hit the first uphill section of pavement, I pushed through it, all the way to the top. The second section, I almost made it to the top before I walked. The third gradual section, I walked. I began to fall asleep standing up. Seven or less miles to go, and I was hitting the wall again. We decided to try a quick nap by the water fill station. I literally fell into the grassy ditch less than 6 inches from the white strip of the road and fell instantly asleep. I woke ten or less minutes later and tried again. I didn’t feel any more rested. Out of the hazy darkness and the slight illumination of my dying headlamp came a wraith, a luminated figure. The Grey Ghost was back with a vengeance. He breezed by me like I was standing still. He didn’t speak a word. He wasn’t even running. He was power hiking at an impossibly fast rate. I couldn’t stay standing, I napped again. I felt defeated.

Music is always the answer at times like these and luckily Grant had come prepared. Pacers are priceless. They can actually function. They can use a phone to do actual tasks and not even drop it three times. Pacers are amazing. We cranked some surprising tunes. Grant luckily liked good music, old music. We jammed to some classic rock of some sort, some folk, I was amazed. The rhythm gave us a pace. I decided that we had to run the last few miles in. We had to catch the Ghost.

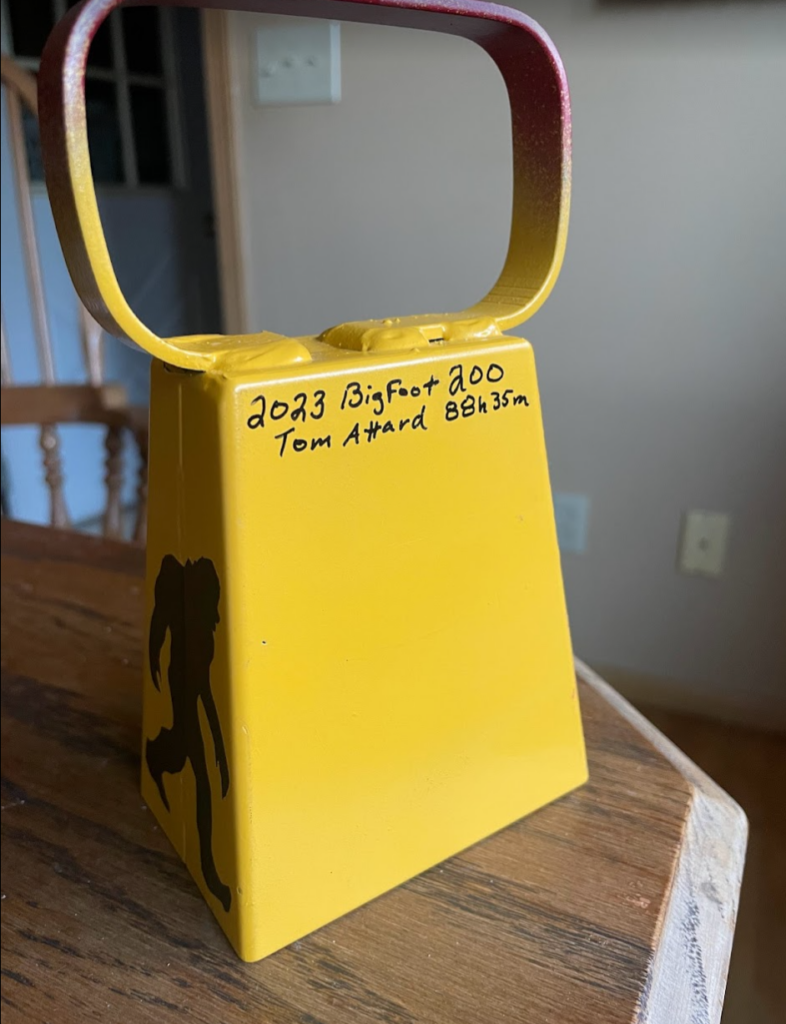

Two miles left and we saw a car parked on the side of the road. A man awoke from within and called out “Who’s there? What are you doing?” It sounded like John Hart. “John is that you?” I called back into the darkness. “TOM ATTARD!” he screamed. “I will meet you at the finish line!” The light came on and the car sped away. We picked up the pace. We were going to put it all out there. We would attempt a sprint finish around the local high school track in Randall Washington. One thirty AM was rapidly approaching. My goal had been to finish in under 100 hours. My dream goal has been to finish in under four days, or 96 hours. My super secret dream goal had been to finish in under 90 hours. I had been in almost constant motion for 88 hours. Only 5 hours of sleep in three nights. Into the parking lot of the high school we rolled in. Mike Zielinski, my crew chief, emerged from the back of his Suburban, half asleep. “Tom?! What are you doing here?! Michael’s not awake.” Grant and I hit the track and started to kick. The race director, cook, and photographer came running out of their sleeping chambers. John Hart hit the field as we arrived. The SPOT tracker had predicted my finish time over an hour later. No one was ready. My wife pulled into the parking lot in a panic. She grabbed our sleeping son and ran for the finish line. Mike got there in the nick of time, but forgot his bell. Grant and I picked up the pace to our maximum speed. Hands up, screaming at the heavens, I crossed the line. High fives were dispensed to all. We had done it! Our team had accomplished something I could have never done alone. I finished the Bigfoot 200, one and a half hours faster than my goal pace, and 17.5 hours faster than I finished the same distance at the Cocodona 250. But where was Amanda? Two minutes too late she came running in with a child in tow. We hugged. She was happy for me, but bummed that she missed the finish. Team work, regardless of how cheesy it has become, truly did make the dream work. (Even in a rugged individual sport like Ultra Running.)

My frail ego wishes I could take all the credit, but it just wouldn’t be right. It is far past time to admit that much of the credit belongs to the thankless heroes, the Pacers and Crews. Most of the time we couldn’t do it without them. Thank you!

Tom Attard is a native Montanan adventure runner, specializing in OKT attempts, in vast tracks of wilderness. Including North-South, solo crossings of the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, and the Bob Marshall Complex. He also has organized several Fundraiser runs for local organizations, including the 100-4-MSLA run, for the American Federation for Suicide Prevention, on his self-created Hundred Mile four-loop course, starting from Silver park in Missoula and climbing the Surrounding Peaks.

He has a bad habit of Ultra Racing. His results vary from Dead Last to a single First Place. All Tom’s running improvements over the years are due to the coaching and training expertise of Kristina Pattison, his coach. His favorite race formats include 200 mile plus races, and twelve-hour mountain climbs. His favorite race is Running Up for Air, Mt. Sentinel Edition.

Tom lives, owns a construction company and trains all here in Missoula Montana. You can find him on local trails (with gain) between the hours of 4-7am November-June.

missoulamarathon.org >>

missoulamarathon.org >>